-

Home

-

News

-

Research Highlights

-

University of California Group Makes a Leap Towards a Clinically Available Source of Spinal Injury Repair Material

University of California Group Makes a Leap Towards a Clinically Available Source of Spinal Injury Repair Material

In the past month, researchers at the University of California and

Veterans Administration San Diego Healthcare System, with partial funding by

the Veterans Administration (VA), demonstrated an important step toward producing components for a promising new technology that could

help Veterans paralyzed by blast injuries regain some motion.1 In animal models, this therapy shows physical repair, and some functional

repair, of substantial damage to the corticospinal tract (CST), the column of neurons within the spinal cord that is the most important

among spinal tracts for voluntary movement.

The work builds on a remarkable collaborative study2 from two years ago including the same group of researchers, in which it was demonstrated

that cells delivered to lesions in rat CSTs could re-establish connections between the brain and the motor neurons that control muscles,

as shown both by microscopic and biochemical examination, and by the recovery of motor control in the partially paralyzed rats. This exciting

result presented two formidable barriers to its exploration as a clinical tool for injured Soldiers (and others): firstly, that the

considerable biochemical differences between humans and rats might make the same technique unworkable, and secondly, that the cells used had

to be specialized "neural progenitor cells" that had developed at least partially into spinal-cord-like cells biochemically similar to those

in the lesion. Such cells must be obtained from tissue in complex processes and can't be maintained in a graft-ready state for extended times,

or scaled up to produce more material, readily available to the clinic on demand.

The research group showed that the first problem might be tractable this past winter, by modifying the earlier work for use in primates.3

Last month's study addresses the availability and scalability problem by using human stem cells that are "pluripotent," meaning they can develop

into a wide variety of tissues. The group tested two types of well-characterized stem cells derived from embryonic tissue and one type made

pluripotent from adult cells, and found that by careful control of the biochemical environment in which the cells are grown, they could be developed

into precursors of spinal cord tissue, similar to the ones they used previously, and that they maintained that identity while grown, scaled, and

maintained for months in the lab. The identity was determined by microscopic examination, biochemical testing, and analysis of gene expression,

to show that the created tissue looks similar to the target cell type.

The lab cells were then tested in the rat model. When implanted into a CST lesion, they grew, developed, and made connections back to cells near

the brain and forward to motor neurons.

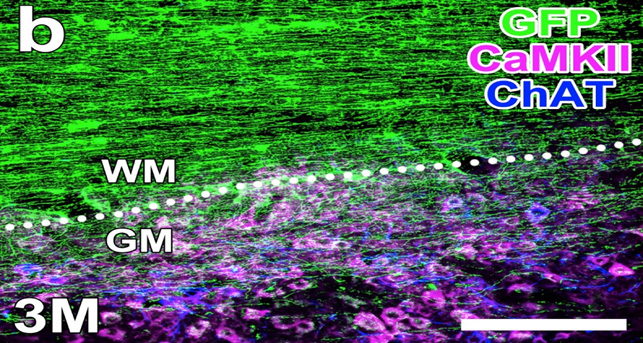

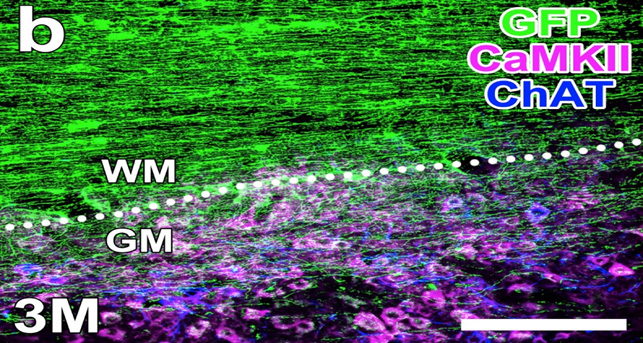

The forward connections were examined microscopically, as new axons – signal transmission routes – were shown to grow from the graft

toward the tail, extending into the "grey matter" of the spinal cord, where motor neurons can receive the signal. (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Healing three months after graft. New, grafted cells were labelled genetically with the green marker. Shown here they have grown new

axons - signaling pathways - down along the white matter of the spinal cord, and those axons are growing into the gray matter, where

they can make connections to the nerve cells that control muscles. The difference between the gray and white matter can be seen because

markers for cell types specific to the gray matter have been "tagged" with antibodies that fluoresce with the labels shown as purple

and blue. (Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Tuszynski)

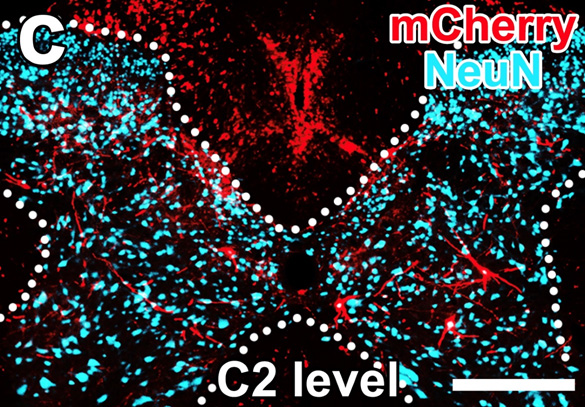

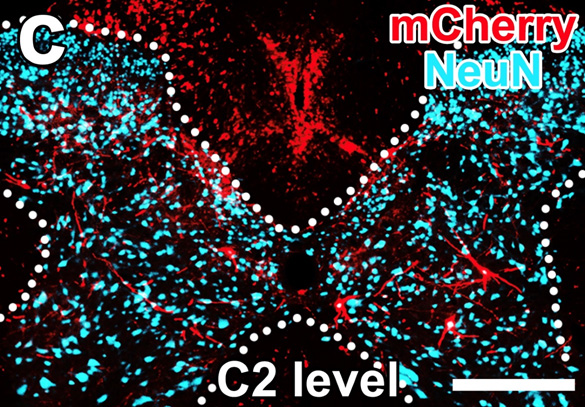

The backward connection was shown by infecting the stem cells with a specially modified and labelled rabies virus, which can travel "upstream" along

neural transmission routes; the virus is able to travel from the grafted cells, back into the brain and brainstem. (Figure 2)

Figure 2:

Four months after grafting, nerves upstream of the graft have made new connections into the new tissue. The graft cells were engineered with

parts of a rabies virus. The partial virus, like the wild rabies virus, can go "backward" along nerve signaling pathways, and is engineered

to carry a gene whose product fluoresces red. Antibodies marked with a label colored blue were used to label cells of a type only found in

the spinal cord (note the horned shape of the spinal cord cross-section!) Nerve cells in the gray matter outside the spinal cord have picked

up the red label, showing that the new cells have become integrated into new neural circuity. (Image courtesy of Dr. Mark Tuszynski)

Corticospinal cells, which deliver the signal from the brain to the spinal cord, were also seen to grow new axons into the graft, re-establishing

the connection, so long as the right cell type is used. Most importantly the graft seems to restore function. The spinal cord injury damages the

rats' hind-limb function, as shown in measures of their gait, behavior, and coordination. The graft partially restores that function.

The new work represents a significant milestone on the way to a promising new therapy. Scalable, storable cells can make this kind of treatment

clinically available and can serve as a source of tissues for testing other therapies and pharmaceuticals that can offer aid to Service Members who

lose motor function on the battlefield.

Notes:

1 H Kumamaru, K Kadoya, AF Adler, Y Takashima, L Graham, G Coppola, and MH Tuszynski (2018),

"Generation and post-injury integration of human spinal

cord neural stem cells," Nature Methods 15:723-731.

2 K Kadoya, P Lu, K Nguyen, C Lee-Kubli, H Kumamaru, L Yao, J Knackert,G Poplawski, JN Dulin, H Strobl, Y Takashima,

J Biane, J Conner, S Zhang, and MH Tuszynski (2016), "Spinal cord

reconstitution with homologous neural grafts enables robust corticospinal regeneration," Nature Medicine 22: 479-487.

3 ES Rosenzweig, JH Brock, P Lu, H Kumamaru, EA Salegio, K Kadoya, JL Weber, JJ Liang, R Moseanko, S Hawbecker, JR Huie,

LA Havton, YS Nout-Lomas, AR Ferguson, MS Beattie, JC Bresnahan, and MH Tuszynski (2018),

"Restorative effects of human neural stem cell grafts on the primate spinal cord,"

Nature Medicine 24: 484-490.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.